How Modern Hip-Hop’s Disrespect Reflects The Spirit Of Punk Music

Since it first lurched out of the boroughs to take the world by storm, hip-hop has had a very clear set of governing principles that were meant to be upheld at all costs. Built on a foundation of respect and authenticity, these two traits– along with an awareness of the founding four elements– were regarded as pre-requisites for a successful career. Paying homage to the past was not only advised but near-mandatory. Referred to in the same way as a warrior’s code, any departures from these sacred commandments would lead to either verbal or physical consequences as you strove to keep your honor intact.

Tupac posing at KMEL Summer Jam, 1992 – Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images

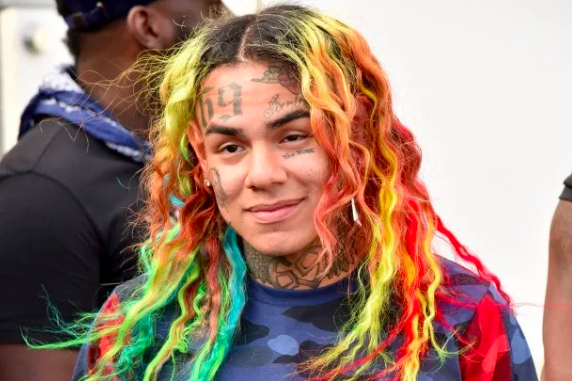

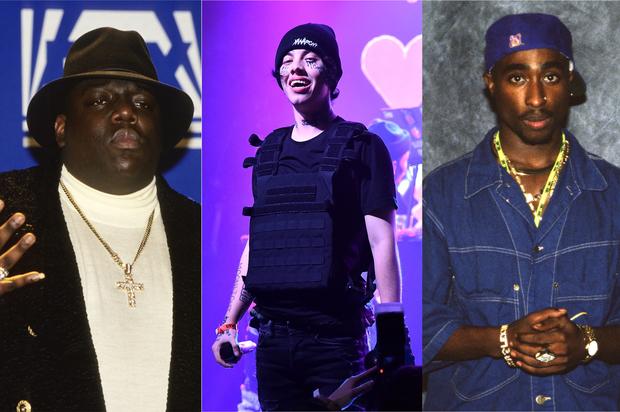

Spearheaded by a new generation of brash and uncompromising artists, these closely-held values are now being degraded from a cultural necessity to a form of outdated scripture. In many ways, this era of indignation and dismissal of the past was instigated by the divisive Lil Xan. Regarded with wariness from the outset, devout hip-hop fans soon had all the relevant evidence to bestow a cultural death sentence on young Diego. Xan declared, without a hint of irony, that the late Tupac Shakur’s output was “boring music” and he quickly incurred rap music’s collective wrath because of it. An irrevocable trespass in the eyes of many, the hip-hop community quickly vocalized their outrage and the debate reached its peak when Waka Flocka and T.I decreed that Xan was “banned” forevermore. Amid all of the uproar, a few scattered voices leaped to his defense and presented a case for clemency.

No stranger to incensing hip-hop fans in his own right, one of the most vocal combatants of the persecution of Lil Xan was his peer and friend Trippie Redd. Relayed over Instagram Live, Trippie believed all of the criticism to be not only unwarranted but irrational:

“Do you see who he is? Of course he don’t like 2Pac … He don’t necessarily gotta like 2Pac to be Hip Hop, nigga. If he think that shit boring, he think that shit boring. That shit is not a part of this new era anyway.”

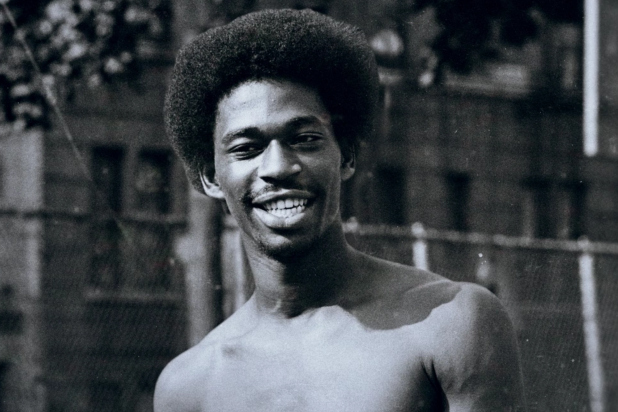

What Trippie couldn’t have known is that his remarks have captured the spirit of a generational shift towards disregarding hip-hop’s longstanding code of conduct. A week before Kodak Black gained the world’s ire with his blatantly disrespectful comments about Nipsey Hussle and Lauren London, the ever-contentious rapper echoed the sentiments of Lil Xan from a year earlier. Once again, the dangerously unfiltered nature of Instagram Live brought Kodak’s barbed tongue to the fore and led to the Project Baby unloading his views on why Biggie and Pac are so revered:

“People tryna say, oh, I can’t put myself in the category with 2Pac and them,” Kodak told his Instagram Live audience. “Actually, I’m better than them n***as. You know why? Like, ’cause, I live what I rap about. Them n***as was just like, them n***as was just legends ’cause they died.”

The Notorious B.I.G at the Billboard Music Awards, 1995 – Larry Busacca/WireImage/Getty Images

In the past, no rapper on the come-up would’ve dared to say something so sacrilegious in fear of alienating their audience and thus lightening their pockets. For this new, defiant generation, they don’t seem to be emulating the stringent self-policed headspace of hip-hop’s past, rather, another rebellious subculture entirely. Formed on the same DIY spirit that empowered today’s internet-spawned artists, the ideology of the UK punk scene of the late 1970’s bears a striking resemblance to the impudence of hip-hop’s new breed. Disenchanted with the pomposity of the world’s biggest rock outfits, the architects of punk regarded the technical wizardry of prog or psychedelia as a pollutant and instead stripped guitar music back to its bare bones.

Conceived of as the antidote to Led Zeppelin, Yes, King Crimson and Pink Floyd among others, the difference in their ethos and sound would soon serve to undermine these fully-established acts. Where the globe-trotting artists of the day were increasingly enamored with complex musical theory and pretentious concept albums, the bands of the emergent underground were working with a maximum of three chords and made their lyricism and melodies punchier and more conversational. Sound familiar?

The Sex Pistols performing live in Copenhagen, 1977 – Keystone/Getty Images

In order to fully illustrate this analogy, the focus will hinge upon two of punk’s most incendiary and beloved bands: The Sex Pistols and The Clash. Concentrated around the Kings Road in London, these two bands made a name for themselves by embodying the unrest and discontent that its youths were experiencing. Although they may not be the first British punk band, the ragtag group of snarling misfits known as the Sex Pistols rejected the status quo and were even banned from their native UK’s airwaves for tracks such as the treasonous “God Save The Queen.” Hounded by the press and the law at every turn, their notorious profanity-laden interview with Bill Grundy courted the same sort of widespread outrage that the unvetted Instagram Live’s of today’s hip-hop artists contend with. Away from the music, their desired destruction of the past bled into their clothing as they donned t-shirts declaring “I HATE PINK FLOYD.” Years on from his tenure as an agent of chaos, The Sex Pistols’ frontman Johnny Rotten conceded that Pink Floyd have “done great stuff” and that he “loves” their seminal Dark Side Of The Moon LP.

Coinciding with The Sex Pistols’ rise was the formation of The Clash. Born of ethnically diverse areas such as Ladbroke Grove and Brixton, the four-piece of Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Paul Simonon, and Topper Headon took the fast-paced barrage and weaponized it to take on social inequalities. In spite of this, they found plenty of time to take aim at the rock music ruling class, seen as an extension of the machine, on “1977.” As blatant as any diss track, the track’s chorus sees Joe venomously bellow “No Elvis, Beatles Or The Rolling Stones.” No matter how scathing it sounded, the late Joe Strummer would later admit that hearing The Rolling Stones in his boarding school dorm room was instrumental in pursuing music as his key concern in life.

Vince Staples performing at ComplexCon, 2018 – Earl Gibson III/Getty Images

Through these historical examples, our current hip-hop artists disdainful renouncement of the past may be easier to comprehend. By vilifying the very artists that they’d grown up on, punk music was unshackling the expectations of what came before them and they were free to forge their own legacy. Unbounded by comparisons or supposed influence, their motivations to destroy and rebuild ensured that they contributed their own distinct fragment to the rich tapestry of musical history. Informed by that same desire to stand on their own two feet, Vince Staples labeling the 90’s greats as “overrated” and Lil Uzi’s vehement refusal to freestyle over a DJ Premier production has a great deal more validity than just cultural naivety. Just like Lil Yachty’s claims that “older hip-hop people don’t understand evolution” or 03 Greedo’s insistence that there’s no onus to pay homage to 2Pac, they’ve all made a concerted effort to distance themselves from the past.

Thus, could it be that the perceived disrespect from new rappers doesn’t come from a place of ignorance but rather, may be informed by an ambition to surpass their predecessors and claim their own spots on the hip-hop Mt. Rushmore? Far from being something to revile, this unwillingness to treat the genre with the solemn, unchangeable respect of a war memorial is pivotal in ensuring that hip-hop doesn’t end up at a creative standstill or fall victim to complacency.